|

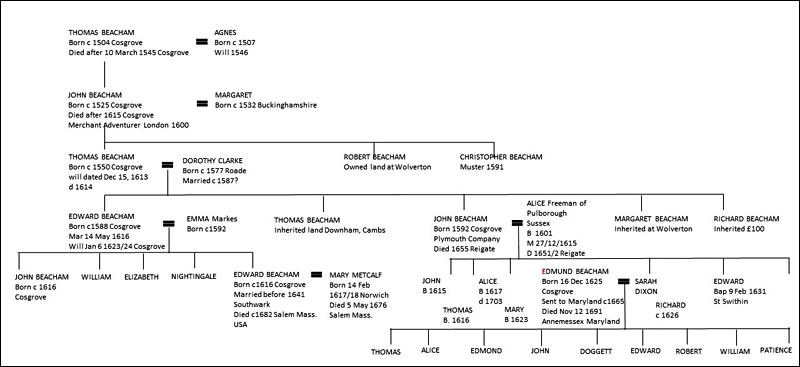

In 1983 DeBrett's of London was commissioned by a descendant of Rhoda Beauchamp Walker, to determine her Beauchamp ancestry.

Quoting from the research work of DeBrett's of London

"Our research into the Beauchamp family of Cosgrove has covered a wide range of sources, the most revealing of which has been a series of Northamptonshire wills in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The will of Edward Beauchamp, the eldest son of Thomas Beauchamp and Dorothy, formerly Clarke, was dated 6 Jan 1624 at Cosgrove, and it was his wish "to be buried in the churchyard of Cosgrove among the burials of my ancestors". He mentioned his wife, Emma, and three sons and two daughters. His father, Thomas Beauchamps's will was dated 15 Dec 1613 and he mentioned four sons, Edward (whose will of 1624 we have just mentioned), Thomas, who was given lands in Downham, Cambridgeshire, and John, the merchant ancestor who married Alice Freeman. Thomas also named a daughter Margaret, who received land at Wolverton, Buckinghamshire. We also learn he had brothers Christopher and Robert.

Thomas's brother, Christopher Beauchamp, left a will in 1622 in which he mentioned his brother Henry. The eldest brother, John Beauchamp, left an interesting will 23 Feb 1615, which was proved in Prerogative Court of Canterbury, the superior probate jurisdiction of England and Wales. Like his nephew and namesake John, son of Thomas Beauchamp, the elder John was a successful merchant. He lived in Amsterdam and although he had a wife, he mentioned no children. He did leave bequest to his nephews, John and Richard, the sons of his late brother, Thomas Beauchamp. The testator also mentioned his brothers, Henry, Christopher, Richard and Robert Beauchamp, and a sister named Ellis. The most important point in the will is that there is a reference to John Beauchamp's father, also called John Beauchamp, who was believed to be living in Buckinghamshire in 1613.

Unfortunately, we know almost nothing about this elder John Beauchamp of Buckinghamshire. However, from the evidence contained in earlier Northamptonshire wills, we believe he can be identified as the son of Thomas and Agnes Beauchamp of Cosgrove. Thomas made his will on 10 Mar 1545, and apart from his son John, he named a daughter Agnes, and his wife, who was also called Agnes. He had a sister called Elizabeth Conqueste. Thomas' widow, Agnes Beauchamp of Cosgrave, made her will on 16 Aug 1545. Most of her property was left to the church, or for charitable purposes, but she did make a bequest to Thomas Conq(u)est, who was her brother, or brother-in-law. Finally, the earliest will we have identified relates to John Beauchamp of Cosgrove, and was dated 16 February 1536. He mentioned his brother, Thomas, who was his executor, his son William and daughter Emma.

Thus we can trace the Beauchamp family of Cosgrove back with a good degree of certainty to 1536 from probate sources. We consulted many other sources, such as Inquisitions Post Mortems, marriage licenses and legal records in the Court of Requests, but these produced no evidence of earlier generations. One source which may have identified the father of Thomas Beauchamp, the earliest known ancestor, is Lay Subsidy Rolls, which are records of taxations levied by Parliament. In 1543/4, Thomas Beauchamp of Cosgrove was assessed for taxation. In 1524/5, we find Richard, John and Thomas Beauchamp at Cosgrove. We know that Thomas and John were brothers, and we may speculate that Richard Beauchamp was their father. However, extensive searches in deeds, muster rolls, pipe rolls, close rolls and other Beauchamp families and individuals flourishing in the fifteenth and sixteenthcenturies, have failed to produce firm evidence of the genealogy before 1536".

|

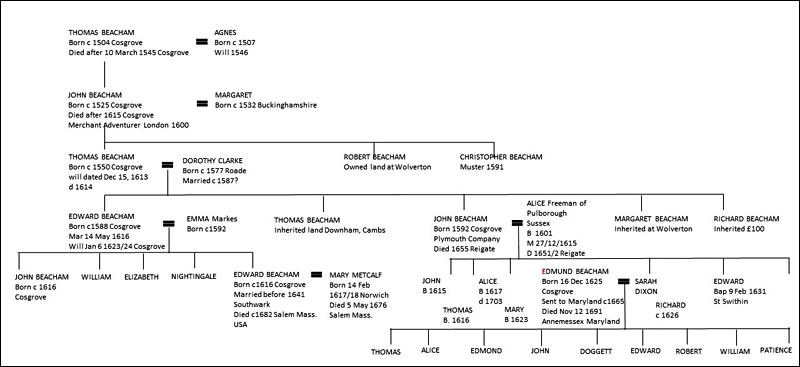

The Beauchamp / BEACHAM Family from Cosgrove

to best reseach 2023

Multiple dates due to calendar changes 1752

|

|

|

|

|

|

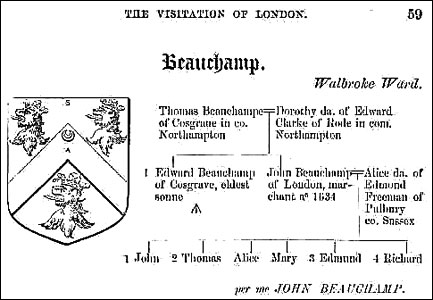

In 1990 Emmet Rice paid for a search in the College of Arms for the coat of arms of John Beauchamp, the Mayflower financier. A coat of arms was awarded to John Beauchamp which bears no resemblance to other Beauchamp coats of arms. In his Herald's visitation John Beauchamp apparently only showed Thomas Beauchamp, his father, in his pedigree. He either did not know his further ancestry or else it was not required at the time.

The coat of arms shows three lions' heads with a chevron separating the upper two from the lower one. The letter from the College of Arms to Emmet Rice detailed a rejection of a certification of this coat of arms to an applicant who was of the family of the Beauchamps of Branston, but it did confirm the ownership of John, the London merchant, to this coat of arms.

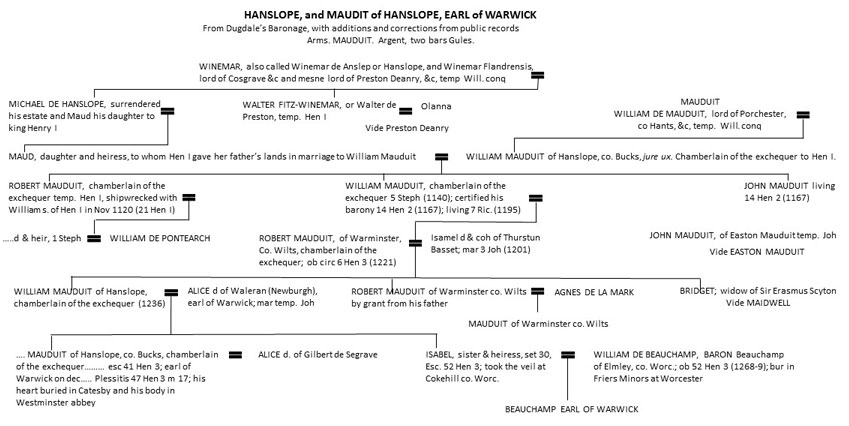

Spellings of “Beauchamp” vary wildly across documents from Cosgrove and Furtho – the Arnold documents recording this family’s propensity for witnessing legal agreements. We assume that these Beauchamps (Beachams) are a yeoman branch at some early stage having split from the noble family which resided at Warwick Castle.

In addition, some internet sources refer to “Sir John Beauchamp and “Lady” Alice – these titles are erroneous, as John was never knighted.

Our first reference to a yeoman Beauchamp in Cosgrove is of William Bechamp of Couesgrave and Alice his wife, who lived in the parish in the first half of the 14th century. William received a grant of land on 6th November 1364, and presumably he and Alice farmed it.

The following notes pertain only to those Beacham(p)s in the direct line of John Beauchamp, the Merchant Adventurer.

Thomas Becham 1504

From Cosgrove wills available to us we can identify Thomas Becham of Cosgrave, born there around 1504. His wife Agnes was born in London around 1507, and Thomas made his will in 1545 in favour of Agnes and his son John, with various bequests to the Parish Church and the Mother Church of Peterborough. The things he left to them confirm that this family were indeed yeoman farmers, inheriting a mare, pots and platters, crops and carts.

In the Lay Subsidy Assessment for the Cleley Hundred of 1524 – 25 the following list shows three “Becham” payers. They represent a considerable proportion of the great and the good in the area at that time.

|

Cuthbert Haversham

|

£7

|

3s. 6d.

|

|

John Becham

|

£5

|

2s. 6d.

|

|

Henry Reve

|

£3

|

18d.

|

|

Richard Rowhead

|

£5

|

2s. 6d.

|

|

John Watson

|

£4

|

2s.

|

|

James Rigby

|

£3

|

18d.

|

|

Richard Becham

|

£20

|

10s.

|

|

Thomas Becham

|

£5

|

2s. 6d.

|

|

Robert Mayhowe

|

£6

|

3s.

|

|

Henry Ryvers

|

£13

|

6s. 8d.

|

|

William Coke

|

£5

|

2s. 6d.

|

|

John Pay

|

£19

|

9s. 6d.

|

It is possible that our Thomas is that in the list above. Thomas died at some point after he had written his will in March 1545, a yeoman leaving pots and platters to his children.

Some speculate that Richard Becham, above, may have been the father of John and Thomas, listed with smaller land holdings. To our knowledge this remains unproven, as do Richard’s origins.

John Beacham c1539

We believe that Thomas’ son John was born in Cosgrove around 1539. His wife was called Margaret, believed to have been born in Buckinghamshire. This may be how Robert, their firstborn, became connected with land in Wolverton.

By 1572 this John Beacham was amongst the leaders of Cosgrove in negotiating “The Release of a highway leading through the Mannor of ffurtho from Covesgrave”, the list of those involved being “Willm ffurthoo cytyzen and grocer of London Hughe Emerson Robt Emerson Henry Rygby John Beacham John Mayhoo and Thomas Spencer of Cosgrave.”

This John’s land clearly ran alongside the Furtho parish boundary, as he was bonded thus:

|

7.

|

29 Sept. 14 Eliz. I. (1572)

|

|

Bond.

John Beacham of Cosgrave husbandman bound in £10 to Thos. Furthoo Esq.,

Condition: Beacham is not to use his passage from Cosgrave to Furtho.

|

There is also a Conveyance from Henry Pedder of Broughton, Bucks. yeoman, son and heir of Thomas Pedder, of the same, deceased, and Elizabeth his wife, daughter and co-heir of Henry Addington and Ann his wife, daughter of Thomas Browne, deceased, to John Becham of Cosgrave, Northants, yeoman; of 19 acres of land in Cosgrave, Potterspury and Furtho, Northants. This is dated 2nd Mar. 1579.

We believe that this John died around 1619 in Cosgrove.

|

|

Thomas Beacham 1550

|

|

John’s son Thomas was born in Cosgrove in 1550, and was a yeoman farmer. There is good evidence that he married Dorothy Clarke of Roade (barely 7 miles north of Cosgrove) around 1587.

Thomas’ will, written 15th December 1613, desired his “body to be buried in the parish church of churchyard of Cosgrave”, which it was following his death on 27th December the same year. Thomas left a considerable amount of money at his death to various children, as well as parcels of land both nearby and in distant counties.

|

|

Uncle John Beauchamp – Amsterdam merchant

In the 1580s, religion was a major issue in Bury St Edmunds. There was conflict between the conservative conformists and the Calvinistic protestants about the appointment of preachers – Handson and Gayton, to the two churches of St Mary’s and St James. Each had a minister (curate) who was paid and a preacher (doctor) who relied on donations. Edmund Freake, Bishop of Norwich (1576-83), and some local landowners were determined to promote conservative conformists, the ‘godly gentry’ like Sir Robert Jermyn of Rushbrooke and Sir John Higham of Barrow wanted protestants. The governors and the feoffees tended to be conservative but the townsfolk, although divided, wanted protestants. Feelings ran so high that during the ‘Bury Stirs’ of the late 1570s and 1580s three petitions were sent to the Privy Council in protest at the dismissal of protestant preachers Handson and Gayton from the churches by the bishop. These were dangerous times – John Copping and Elias Thacker were hanged in July 1583 for their extreme protestant views.

Such full blooded Calvinism may well have been the motivating force behind the decision taken by Thomas, his son, John Beacham, his supervisor, and William Mumplayne, one of his witnesses, to enlist in support of the preachers Handson and Gayton in 1582.3°

Thomas Beacham and his son John are believed to be ancestors of John Beauchamp, Merchant of Amsterdam, and his nephew John Beauchamp, the Mayflower investor. They were all born in Cosgrove and their involvement in the Bury Stirs probably confirms their long held rejection of the Church of England.

We know that John Beauchamp of Amsterdam, uncle of John Beauchamp, the Mayflower investor, was a follower of Robert Browne, born in Rutland c1550. Browne was the first seceder from the Church of England and the first to found a church of his own on Congregational principles. By 1581 he had attempted to set up a separate church in Norwich; he was arrested but released on the advice of William Cecil, his kinsman. Browne and companions left England and moved to Middelburg in the Netherlands later in 1581. There they organised a church on what they conceived to be the New Testament model, but the community broke up within two years owing to internal dissensions.

Browne had deep connections in Northampton. In his later life he returned to the Church of England and is buried in St Giles’ churchyard Northampton.

The Early English Dissenters in the Light of Recent Research (1550-1641)

Volume i History and Criticism by Champlin Burrage

We may here also mention some of those less known early Brownists who renounced their opinions, but who instead of returning to the Church of England, wandered still further away, and presumably sought to make converts to their particular views. Among them should be included those “vvandering brethren, (vvandering starres”), who, even before 1603, according to George Johnson, went “hither and thither, to and from England, abiding in no certaine place.” These were John Beacham, William Shepherd, John Nicholas, Richard Paris, David Bristoe, and William Houlder.

The Rev Dr Henry M Dexter constructed a list of “English Exiles in Amsterdam” from 1597 to 1625. This list includes:

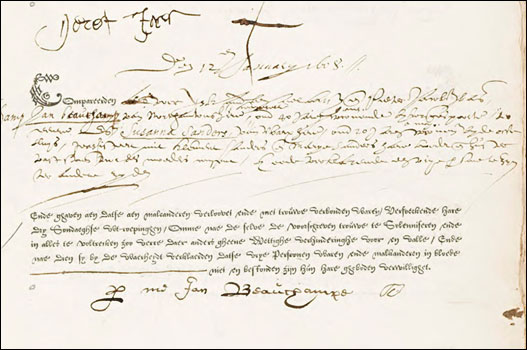

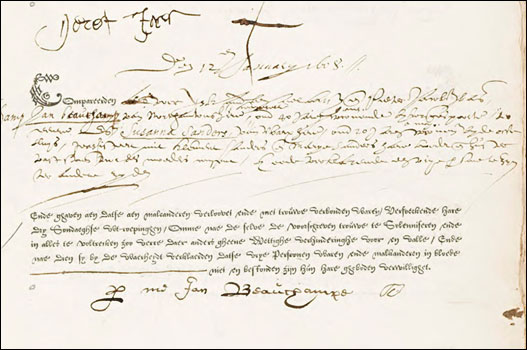

This image shows Uncle John as Jan Beacham, the name later crossed out and the Norman version "Beauchamp" added.

Beacham, John [from Northamptonshire] Amsterdam Marriage Records Jan 12, 1608.

Beacham, Susanna [Sanders] [from Warwickshire] Amsterdam Marriage Records Jan 12, 1608.

Will of John Beacham of Amsterdam 1615

John Beauchamp 1592

The will of Thomas Beacham names five of his children, although their dates are uncertain in three cases. It is certain that his son John, born in 1592, in Cosgrove, was a younger son.

| 28 November 1598 |

9:00 A.M. |

Beauchamp and John Beauchamp |

6 yeres old or 7. about wheate harvest or first lad[ye] this child is troubled wth a Cough & hoping so sore yt it forceth him to cast vp his meate. he hath a good stomack to eate & digest his meate but his cough fetcheth all vp againe

from the bottome of his belly. pater filio sine consensu. November 28 die ♂ h. 9. 1598. |

In the entry above, from Richard Napier's casebook, we can see the young John Beauchamp was taken to the physician at Great Linford for his Whooping Cough. This is so far the only mention of John in his home village. [Cosgrove Health & Medicine]

In his father’s will John is mentioned thus:

“Item : I give and bequeath to my son John Beacham my estate, right title and interest in my house in Sisaw(?) with the pertenance or else four score pounds of good and lawful money of England.”

We believe that this property may have been in Syresham, about 15 miles west of Cosgrove. Having left Cosgrove as a young man to make his life in London, John was apprenticed as a Salter. He evidently valued his membership of the Salter’s Company all his life, as will be seen later. He did not stay within his own trade, however, and began dealing in cloth and other goods as an “interloper”.

|

|

|

|

|

We know that John was already a man of property and a little wealth at the time of his marriage in December 1615 to Alice Freeman daughter of Edmund I Freeman and Alice Coles of Pulborough in Sussex. John was 23 and Alice was possibly, born in 1601, only 14 years old.

|

|

Their first child, a son, was born in the year 1615/16, so it is also possible that Alice was already expecting this child at their marriage. Over the next eight years another four children were born to the young couple, who were based in Pulborough, probably with Alice’s family. These were Thomas, born 1616, Thomas, born 1617, Alice, baptised 22 June 1617 and Mary, born 1623. It was whilst the family were at Pulborough that the Mayflower voyage took place. |

Nick Bunker, in “Making Haste from Babylon: The Mayflower Pilgrims and their World – A New History” (published by Pimlico 2011), says that one of John’s brothers was a London Haberdasher. John’s uncle was another John Beauchamp, merchant of Amsterdam, who left John 2000 guilders at his death in 1615, as well as some London house contents and the management of a further 5100 guilders “of the severall Institucion and substitucion” for two years.

|

|

|

John was therefore very well placed to trade in haberdashers’ items from Holland. Nick Bunker describes how “Within less than a decade, Beauchamp rose to become by far the largest importer of the sort of goods carried by a travelling salesman. With his roots in the countryside, Beauchamp began by sending rural commodities to Amsterdam: fleeces, horsehair, and black rabbit skins. Using Dutch ships, he exported stockings, of the kind farming families knit by the fireside as a way to earn a little extra money. Then back from Holland he brought merchandise to feed the peddlers of the kingdom as they built their networks of consumption, selling lightweight articles to housewives and provincial shopkeepers.

In 1621, we find Beauchamp importing from Holland an assortment of tennis balls, pins, needles for securing bundles on a horse’s back, and six thousand thimbles. Ship after ship sailed into the Thames carrying items for John Beauchamp. Among them were hundreds of the “inkles” and “caddisses” found among the wares sold: an inkle was linen tape used by seamstresses, and a caddis was woollen tape for stocking garters. We find, for example, the Cornelius of Amsterdam unloading for Beauchamp a cargo of caddis ribbons, inkles, hairy goat skins, plates, sewing needles, nearly seventeen thousand thimbles, and more than 200,000 tacks.”

|

|

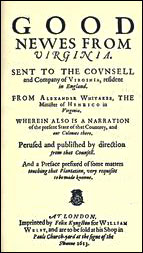

For many years, during John Beauchamp’s merchant enterprises, tracts had been published, telling investors about the wonderful opportunities in the Virginia Plantations. “Good News from Virginia” was published by Whittaker in 1613, and “True Discourse of the Present Estate of Virginia”, by Hamor in 1615. A group of Merchant Adventurers gathered in London to sponsor and finance an expedition to send Separatist farmers across the Atlantic. Their agent in London was Thomas Weston, a successful, wealthy iron merchant.

The Pilgrims respected and trusted Weston, who formed a joint-stock company to handle the financial matters. When Weston and the Adventurers agreed to finance the trip, they purchased shares so that they could remain in England while the would-be Colonists agreed to contribute their services at a certain flat fee. They would work as traders or fisherman for seven years, sending back furs, lumber, and other resources so that Weston and the others could profit from it. All of their profits would be placed in a common stock fund and no land would be assigned to anyone.

The Merchant Adventurers of London were able to take complete advantage of the Pilgrims and they weren’t able to profit from their hard work. Yet, the chance to live in a new land had been too tempting for most, so they signed the agreement and the trip to America was financed.

|

|

|

|

The Mayflower sailed in 1620, and the winter of 1621 / 22 Thomas Weston managed to send another small craft, the Sparrow, across the Atlantic with financial help from Beauchamp. The next few years were hard indeed for the first Plymouth Colonists.

In 1624 four Adventurers sent a statement of affairs to the Plymouth colony explaining why most of the backers had given up on them through losses at sea and failed profits. These four, including John Beauchamp, asked that after the colonist's needs were filled that "you gather together such commodities as ye cuntrie yields and send them over to pay debts and ingagements which are not less than £1400."By 1626 the Plymouth colony was in deep financial trouble.

|

|

A Mayflower passenger, Isaac Allerton, was sent to sign a new deal with the 41 investors who remained. All the original capital from 1620 was written off. It was agreed that the debt owed by the Pilgrims would now be £1800, to be repaid in nine instalments every September up to 1636 to five men led by Pocock and Beauchamp, acting for the rest of the London investors. Since the Adventurers had already laid out some £7,000, this was a considerable loss to them.

The four Merchant Adventurers who retained their interest in the affairs of Plymouth Colony were James Sherley, Richard Andrews, Timothy Hamerly and John Beauchamp, and were later known as the English Partners of the Purchasers. In return the investors at home gave up all claims to all “the said stocks, shares, lands, marchandise and chatles” in the Plymouth plantation.

|

|

|

In July 1627 a small group known as “Undertakers”, led by Bradford, Standish and Allerton, and with others including John Howland, agreed to pay the sums required in London and became personally liable in the event of the default. In return the undertakers would get the profits of the trade in beaver fur for six years for the whole colony, as well as profits from corn and tobacco. After 1633, the agreement would be reassessed by the whole colony. In the meantime additional loans at high interest came from Beauchamp, Sherley, Pocock and others.

James Sherley, Goldsmith, and John Beauchamp, then known as a Salter of London, were named as agents of the Plymouth colony to receive all goods and merchandise sent to England, and to sell or barter their wares. These agents were also to purchase supplies for New England.

|

|

|

|

|

|

John Beauchamp’s family continued to grow. On 16th December 1625 a son, Edmund, is believed to have been born, but his place of birth is uncertain. By 1630 John’s family appear to have moved to London, to an area near the Salter’s Hall. A stillborn daughter was registered that year at St Swithin’s London Stone, directly behind the Salter’s Hall, which had a room above let out for Dissenters’ meetings. It is not clear whether John Beauchamp had non-conformist leanings – all his children were baptised by the Church of England. Six more children were recorded as baptised at St Swithin’s during the next nine years. |

|

|

|

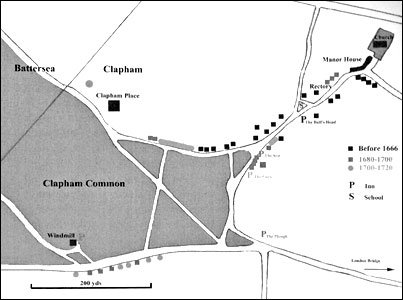

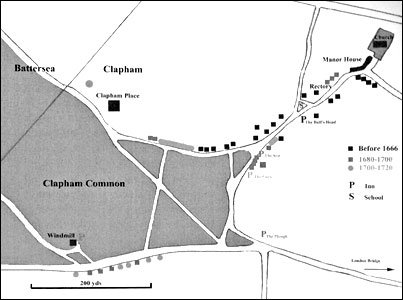

In 1633 John Beauchamp and James Sherley took a lease together on a house in a group of properties on an estate in Clapham called Brick Place. This area was dominated by a group of “radical Puritan merchants” and is described in detail by Timothy Walker in his book “The Clapham Saints” published in 2016. This arrangement seems to have been an attempt by Beauchamp and Sherley to conduct business amongst a group of like-minded investors, indicating their social standing at the time. In the same year Beauchamp was recorded in the Visitation of London as serving in local government in Walbroke Ward, but we know that Alice, his daughter did live with her father at Clapham, and married John Doggett, who had moved into the Clapham area, some years later. Timothy Walker’s book gives a fascinating insight into their Clapham home, later renamed Clapham Place. Shown below:

Clapham Place

In the same year that Beauchamp and Sherley leased property at Brick House in Clapham, 1633, land transactions were in discussion in the Plymouth Colony, and the Undertakers were waiting on the four Adventurers Andrews, Beauchamp, Hatherley and Sherley to declare their preferences for land before allocating tracts in the Scituate area, promised to them in 1627. Timothy Hatherley did become a resident of Scituate, and bought out the shares of Beauchamp and Andrews, evidenced by a document of 1646.

The working relationship between Beauchamp and Sherley disintegrated in 1636, when the Colonists claimed that their repayments had all been made, but John Beauchamp and Richard Andrews had received no money since 1631 when each had lost £1100. The settlers sent beaver pelts to London from which Beauchamp was able to recoup £400. Beauchamp and Andrews took Sherley to court to accuse him of keeping £12000 for furs which he had no accounts for – but Sherley won the case.

By 1641 all parties in the Plymouth affair wanted their freedom. The remaining joint stock, consisting of housing, boats, implements and commodities was valued at £1400. This was shared by the London partners. The Plymouth leaders agreed to pay the London partners £1200 to be paid £400 down and £200 per year to settle the whole debt.

John Beauchamp’s daughter Alice married John Doggett on 10th August 1643, at Wandsworth St Mary, Battersea, London. This family were to become significant antecedents of citizens of the New World.

In 1645 John received the equivalent of £210 in the form of houses and lands in Plymouth from Bradford, Prence, Standish and Winslow, recorded in the Plymouth Colony Deeds. Most people might have written off their association with the venture at this point, but it seems that John Beauchamp persisted in his connection with the Colony.

At home, in the same year, John’s son Thomas married Sarah Felps in Reigate – recorded in Boyd's Marriage Index. 3d Series. This may have been the beginning of the Beauchamp family moving to this town.

Only two years later in 1647 Thomas died in Reigate. Back in London, John apprenticed his son Edmund with John Doggett as a Mercer for 8 years from 19th March, using his membership of the Salters to confirm the contract.

In his volume “Reigate : Its Story Through the Ages” published in 1945, Wilfred Hooper of the Surrey Archaeological Society explains:

In 1648 Parliament [under Oliver Cromwell] attempted to organise the Churches of Surrey on a Presbyterian basis…….

Surrey was divided into six classes or Presbyteries of which the sixth, or Reigate class comprised the town of Reigate and other towns and villages in the Hundreds of Reigate and Tandridge.

The local members included Mr Parr, the vicar, and Messrs Roger James, John Parker and John Beauchamp. But the scheme never took root.

In his last years, John Beauchamp’s work as a magistrate was again noted by Hooper :

During the Commonwealth and Protectorate the religious ceremony of marriage was abolished and after 1653 weddings were celebrated by a Justice of the Peace. These civil unions were performed at the church after publication of notice on three successive Sundays in church or on three successive market days in the Market Place. Two local magistrates, John Beauchamp and Thomas Moore, usually officiated. Beauchamp was a Presbyterian and Moore, who lived at Hartswood, an early member of the Society of Friends.

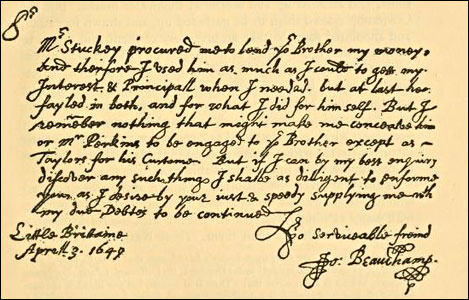

Of all the Mayflower expedition’s investors, John Beauchamp seems to have had the longest involvement. In 1649 he wrote a letter:

|

|

|

|

|

| Sir,

Mr Stuckey procured me to lend your Brother my money bond therefore I used him as much as I could to get my Interest & Principall when I needed, but at last he fayled in both and for what I did for himself. But I remember nothing that might make me conceive him or Mr Perkins to be engaged to your Brother except as Taylors for his Custom. But if I can by my best enquiry discover any such things I shall be as diligent to informe you, as I desire by your just & speedy supplying me with pay due, Debts to be continued,

Little Brittaine

Aprill 3 1649 Your serviceable freind

John Beauchamp

At this time he was evidently conducting business in another small area of London near to St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

|

|

|

| John’s family were by this time well established in Reigate, and, during the next eight years, significant family events are recorded in the town. In 1650 John’s daughter Mary married Walter Wolsey in Reigate. John’s wife Alice’s father had died, and by 1651 Alice’s widowed mother Alice Cole Freeman was living in Reigate with them. Alice herself died the same year at the age of 50, leaving John widowed after a marriage of 36 years – a great length for the period.

John’s health failed him, and he wrote his will in “the frailtie of my own health and the certaintie of Death and uncertaintie of the time of my departure”, before his death at the age of 63, still at Reigate, in 1655.

It is assumed that he was buried in St Mary’s Church in that town. No records of his burial exist, presumably as his requested in he will

First I humbly beseech Almightie God to take and (receive?) my Soul into his mercifull protection And as to my bodie I desire the same may be buryed in a decent manner without coffin (?) funerals or (…) pomp.

|

|

|

John’s will remembers his home village – supremely significant in those days, and he left “to the poor of the parish of Cosgrave in Northamptonshire where I was born the sum of four pounds of the lawfull money of England to be paid within one month after my death And to be distributed equally among the poor of the said parish by my (good?) Cozen Beauchamp now living or the survivor of them or in Case both of them shall be dead at the tyme of my decease then to be distributed by the Overseer for the poor of the said parish for the time being.” The poor of Reigate received five pounds from John, indicating his commitment to his new town.

All John’s children received substantial sums of money, although some more than others, and the will was constructed on the understanding that “Coppiehold Lands Tenements and hereditiments” would be sold to achieve this. John Beauchamp appeared to be a man to whom property was relatively unimportant.

|

|

After John’s death his son George was apprenticed on 17th June 1656 to Thomas Wickes as a Mercer for 7 years, at Paternoster Row in London. It is not known who sponsored him, but in the same year his brother Edmund was made a Freeman of London, so the family must have been trusted and highly regarded.

|

|

|

Seven years later George married Sarah Higham in Rempleton, Nottinghamshire on 7th December 1663 – recorded in Boyd's Marriage Index, 3d Series. The couple settled in Nottinghamshire and it is thought that George never did receive the full legacy of his father’s will.

In 1665 John’s son Edmund travelled to America, shortly before the Fire of London in 1666. This catastrophe destroyed the Church of St Swithin’s at London Stone, which must have devastated the family, for whom it was a spiritual focus.

We know that Edmund married Sarah Dixon in Somerset County Maryland in 1668, and from thence the Beauchamp story is well documented by their American descendants, as is that of the descendants of Alice Beauchamp and John Doggett.

Back in Cosgrove, some of John's father's other sons continued to farm and to apprentice their sons. The following reference is from the London Carpenters' Company records :

5 November 1667

32 Valentinus Beacham filius Johannis Beacham nuper de Cosgrave in Com Northton agr. defct po: se appren Benjamin Spencer de Crutched friers pro 7 ann a die dat. etc.

|

|

Beauchamp wills. (Northamptonshire Record Office N/P N)

| Surname |

Forename |

Status |

Place |

Year |

Type

|

N/P |

Series |

Book |

No. |

fo/pg |

MW |

Notes |

| BECHAM |

John |

|

Cosgrove |

1536 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Debrett link |

| BEACHAM |

Thomas |

yeoman |

Cosgrove |

1614 |

|

N |

1st |

Y |

|

249 |

18 |

|

| BEACHAMP |

Edward |

|

Cosgrove |

1624 |

W

|

N |

1st |

AV |

|

205 |

23 |

|

| BEACHOM |

Christopher |

yeoman |

Cosgrave |

1622 |

W

|

N |

2nd |

M |

|

247 |

35 |

|

| BEAUCHAMP |

Anne |

widow |

Cosgrave |

1667 |

A+I

|

N |

|

bundle |

|

|

|

not found |

| BEAUCHAMP |

John |

jun |

Cosgrave |

1684 |

|

N |

|

bundle |

33 |

|

|

|

| BEAUCHAMPE |

Anne |

widow |

Cosgrave |

1667 |

|

N |

4th |

2 |

|

11 |

66 |

|

| BECHAM |

John |

|

Cosgrove |

1532 |

|

N |

1st |

D |

1067 |

419 |

4 |

|

| BECHAM |

Thomas |

|

Cosgrove |

1545 |

|

N |

1st |

I |

7 |

5 |

7 |

|

| BECHAM |

Agnes |

|

Cosgrove |

1546 |

|

N |

1st |

I |

527 |

206 |

7 |

|

Beauchamp wills held at The National Archives

| Surname |

Forename |

Status |

Place |

Year |

Date |

Ref: |

| BEACHAM |

Thomas |

yeoman |

Cosgrove |

1614 |

May 04 |

PROB 11/123/409 |

| BEAUCHAMP |

John |

yeoman |

Cosgrove |

1655 |

Jul 14 |

PROB 11/244/665 |

| BEAUCHAMP |

John |

|

Reigate |

1655 |

May 23 |

PROB 11/245/407 |

| BEAUCHAMP |

John |

yeoman |

Cosgrove |

1655 |

Jul 14 |

PROB 11/224/287 |

| BEAUCHAMP |

John |

gentleman |

Cosgrove |

1688 |

Jul 06 |

PROB 11/392/68 |

|

|