|

From “Cosgrove – The History of a Village” by Gwen Brown, nee Jelley [1991]

Chapter Six “Between the Wars”

For the earliest settlers, one of the great advantages of Cosgrove’s site was the availability of water, which could be drawn from the beds of limestone that outcrops on the valley side. In the early decades of the 20th century there were at least 16 wells in use, each with its long case pump to raise the water, often from great depths.

Most of the cottages were arranged in groups facing on to a communal yard, where the pump was centrally placed, and where there might also be garden plots, pigsties, lavatories and barns. This arrangement did not make for privacy - everyone knew his neighbours business! Most of those clusters of houses have now gone. There was one on what is now the Barley Mow car park, and other between the Barley Mow and the aqueduct [or horse tunnel], and another behind the old school to name but a few.

The individual cottage was very small. Typically, the outside door led directly into the living room, no more than 10 feet square. Here the family spent most of its time, for it was kitchen, dining room and sitting room combined. The range provided warmth and cooking facilities. The scrubbed deal table served as the pastry board and then, food preparation finished, it would be covered with a chenille cloth and, on top of that, at mealtimes, a white cloth. Upholstered chairs were rare, but there would usually be a large wooden rocking chair-for the head of the house only! The others had to manage with a small sofa and the wooden dining chairs around the table. The quarry tiled floor was rarely carpeted, and a rag rug in front of the fire would provide a modicum of comfort. The rag rug was made in the same way as the home made woollen rug of today, but instead of special canvas, the base was an opened out grain sack, begged from the local farmer. Into this sacking, strips of rag were pegged exactly as the length of thick wool are pegged into canvas, with a tool called a latch hook. Outworn and outgrown trousers, jackets and skirts were cut into pieces about six inches long by one inch wide and these, knotted into the sacking, made a hardwearing mat of drab but serviceable colour.

Behind the living room there was a tiny scullery, equipped with a coper and a shallow earthenware sink (with outlet but no taps) and just about space for a paraffin coper which became common in the thirties as the preferred method of cooking.

A door in the living room gave access to the steep wooden stair way which led to two small bedrooms, a state like with their low and sloping ceilings. It seems likely that the houses were originally single Storey, with the ground floor open to the rafters, but probably in the 18th century the upper floor had been inserted and the line of the thatch altered to accommodate first floor windows.

In these cottages there was no gas, electricity or piped water before the mid thirties. Cooking was done on the kitchen range or the paraffin stove, and frequently the Sunday joint was taken to the Bakehouse to be roasted in the bread oven. Village was much less varied than it is today, mainly because of lack of refrigeration facilities. The one village shop sold basic groceries; meets could be purchased from the travelling butcher’s van which came twice a week, and from the mid twenties the bus service made the shops of Stony Stratford and Wolverton accessible. Most cottages and farmers would have home killed pork and home cured bacon, together with vegetables from garden or allotment. Potatoes, onions and carrots could be stored, but most other vegetables were eaten only when in season. Good use was made of wild fruits and most people went black-berrying or crab-appling. Elder berries make good wine and wild mushrooms were a great treat.

Every drop of water had to be pumped and carried into the house in pails. On wash days, the copper in the scullery had to be filled and the fire underneath it lit, early in the morning, to get water hot enough to wash the linen. Trimming and filling the oil lamps was a daily chore, as was the chopping of firewood and bringing in the coal from the barn.

No piped water meant no flush toilets. The privy was a small brick hut at the farthest end of the yard or garden. It housed a scrubbed, wooden, box like seat with a round hole cut in the top and a small door at the front, through which the bucket could be removed for emptying. Daylight filtered in through small, diamond shaped, holes cut high up the hut door, but at night it was pitch dark. Once a week, the “night cart” came round. It was a cylindrical metal tank mounted horizontally on a wheeled axle and horse-drawn. The “night cart men” would go to each privy to collect the bucket and empty it into the tank, waking the village with a clang and clatter.

By about 1936, electricity was available in Cosgrove, and electric irons, cookers and vacuum cleaners began to appear, they fridges were rare until after the war. Us about the same time, the village got mains water. Few cottages actually had it laid on - perhaps the landlords would not pay - but some of the old pumps were replaced by standpoint from which water would flow at the turn of the lever. This was considerably less arduous than pumping, but the water is still had to be carried home in buckets. In the years immediately prior to the 1939 war, new council houses were built along bridge road and supplied with mains water and electricity, and as people moved into them from the old cottages, there was less and less demand for the communal standpoints. The cottages were condemned by the public health authority as being unfit for habitation and by the 1950s almost all had been demolished and many of the wells sealed off.

Farming in the 1920s was far less mechanised than it is today, although some machinery was used and the number of farm workers had declined drastically since the 1870s. Cosgrove farmers kept sheep and cattle and grew serials, hay and groups. Cows were still milked by hand and the milk sold, and pasteurised, at the dairy door. Every farm yard had milking shed, pigsties, a muck heap and barnyard hens strutting around, nesting where they liked - the farmer and his family knowing all the likely places to look for the eggs.

Tractors were rare, and combine harvesters non-existent in the neighbourhood. At harvest time, the edges of the cornfield were first scythed to prevent trampling and then the horse-drawn binding machine would cut the corn, bind it into sheaves and eject those sheaves as it moved around the field. This was done before the corn was completely ripe, to avoid the shedding of the grain, and the sheaves would be stooked to finish ripening and drying. A stook was a wigwam like arrangement of six or eight sheaves, the making of which was heavy, dusty and back breaking work. Stooks of oats were traditionally supposed to stay out in the field for three Sundays; wheat was left for one or two weeks depending on the weather. There was no chemical weed control, and the more weed, the longer the stooks took to dry. Then the sheaves were taken by horse and cart to the rick-yard where they were piled into a rick, sometimes circular, sometimes rectangular, and thatched with straw to keep out the rain. In this way, the corn would await the steam threshing machine, which went the rounds of the local farms in the autumn. Once the last sheaf had gone to the yard, the field was opened for the gleaning and the village women would flock there to gather up all the stray ears of corn - free food for their backyard hens.

Hay was also cut mechanically, but while it was drying on the ground, farm workers armed with pitchforks would turn it several times to ensure thorough drying before it too was made into a rick and stored for winter fodder. Rick building was an enormously skilled job - a country craft that must almost have died out now that the corn is combined and grass can be made into silage.

Like the cornfields, hay fields and permanent pasture were uncontaminated by chemical weed killers, so wild flowers were abundant everywhere. There were scarlet poppies among the wheat; buttercups, daisies, clovers and trefoil was in the meadows and the hedgerows were bright with violets, cuckoo pint, ground ivy and masses of cow parsley known locally as keck, (obviously a corruption of its alternative name, kex). Before the ravages of the Dutch disease magnificent elm trees were common in the hedges. One giant specimen stood at the Dog’s Mouth road junction, another at the Castlethorpe turn and several others near the canal bridge. Their demise has made a noticeable difference to the landscape.

Fashions changed only slowly in those days, and although short skirts and short hair were in vogue, the older ladies still wore ankle length dresses, usually black, and had their long hair twisted into a bun in the nape of the neck. None of them would have dreamt of going out without a hat on, and a few of them wore a man’s cloth cap while pottering in the garden. Men’s clothes often reflected their occupation. Farmers would work in tough corduroy trousers and hobnail boots, but would dress up to go to Northampton cattle market in tweed suit, leather gaiters, collar and tie and tweed cap. There was not the variety of good waterproof clothing that we know today and farmworkers, when out in the fields, used old sacks, cut to form a hood, to protect head and shoulders from the rain. The off duty butler or farm bailiff might be seen out in the village in a dark suit and bowler hat, but the average working man wore a cloth cap and a muffler. Men’s shirts always had a narrow neck band and separate - usually stiff - collar to be attached with studs front and back, but the collar would only be worn for best, not to go to work. Small businessmen, like the baker or the postmaster, would never be seen out without collar and tie - that was their status symbol - and they almost always wore a three piece suit, the waistcoat embellished by a gold watch chain.

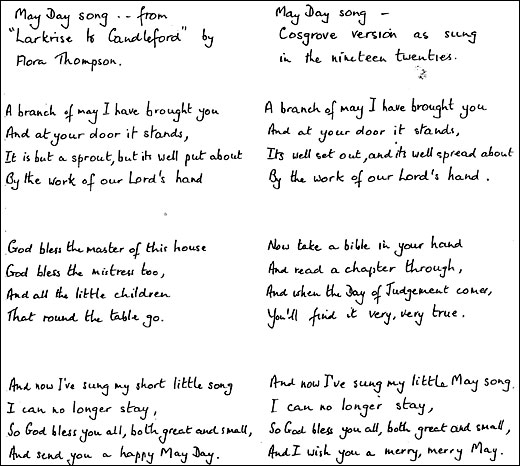

If Cosgrove had ever known typical village customs like maypole dancing or harvest suppers, these things had died out by the 1920s. May Day was still celebrated up to about 1925, but not with a traditional dancing. The school teachers and the children together would choose a May Queen who would wear her best frock and be crowned with a wreath of flowers. Led by the queen, all the children would process around the village, carrying wooden hoops garlanded with flowers and greenery, and at every house they would sing the Maying Song. By 1930 custom had lapsed and few even remembered the words of the song.

Feast Sunday was in July - and earlier in the century there had often been a celebratory fair in the Barley Mow fields, with roundabouts, swing boats and coconut shies, but by the early 1920s this had lapsed. Most cottage gardens grew Madonna lilies and these were carefully monitored all through early July, for they were supposed to be in bloom for the Feast. It would be interesting to know if, and Howell, feast Sunday had been celebrated in earlier years, and also why this particular Sunday in July should have been so designated. In many places an event of this nature commemorates the patron saint of the church, but neither Peter nor poor of Cosgrove church is designation as his special day in July, and the date seems rather too early in the year to have grown out of an old Harvest-home thanksgiving. So Cosgrove’s feast Sunday remains something of a mystery.

[St Peter’s Day was 15th July under the old calendar]

The 1920s and 1930s were years of depression, and life for the average villager was hard. Working hours were long, wages low, and holidays rare. For entertainments there was the “wireless”, and the men could spend evenings at the pubs where a few pence would buy a pint of beer and a friendly game of darts, dominoes, cards or table skittles, the latter being peculiar to the North Bucks and South Northants area. There was the occasional visit to the pictures at Stony Stratford, but a two mile walk there and back on a dark winter’s night did not encourage frequent cinema going. In the 1930s a branch of the Women’s Institute was established and this gave the housewife an afternoon out, once a month.

Not until 1915 did Cosgrove get street lighting, street names and house numbers. Before that, letters would be addressed to, say, Mrs. Clarke, Barley Mow cottages, or Mr. Williams, The Green, and it was left to the poor postman to remember who occupied which house.

Sometime in the early 1920s, Mr. Whiting of the Lodge Farm abandoned agriculture and developed the sand and gravel deposits on his land. These pits provided about a dozen jobs and brought more traffic to the village streets as lorries plied to and fro. But most of the wage earners still went to Wolverton. By this time few actually walked; some cycled along the “bank” as the canal towpath was called, but by 1923, Malcolm Jelley and instituted a daily bus service especially to convey workers to and from Wolverton. In addition to the workmen’s bus, there was a Friday Service to Wolverton market and a twice weekly service to London, so that during much of the interwar period, Cosgrove was better served by public transport than at any time before or since.

|